Introduction

The idea of being inside a laboratory might seem anathema to many ultra-runners. We often live for the outdoors and take part in a sport that is beyond the realms of what is normally considered possible. What makes us different can’t possibly be explained by a scientist, some would say.

Yet increasingly we are seeing ultra-endurance athletes embracing the value of a scientific approach. As competition levels increase, nutrition advice gets better, and experienced coaching brings athletes to new personal bests, more athletes are embracing the lab.

(Hour 7 athlete Damian Carr in the lab preparing for a 24 hour race)

All about the VO2 Max?

The most common reason you might hear an athlete has been in the lab, is a VO2 Max test. The maximum amount of oxygen your body can use per minute. The bigger the number, the better you look on social media.

While there can be a useful psychological boost from a VO2 Max test (or a crushing disappointment if perhaps we hoped for better) it’s not the most useful thing we can find out, especially for ultra-runners and other endurance sportspeople. Factors such as just how much of that oxygen you can actually use, how efficiently you are using it, and what you are using to fuel that effort can be a lot more useful to us.

Just how often do you think an ultra-runner is reaching their VO2 Max in racing, or even training?

Not everything that is measurable is worth measuring

So what is the best use of our time if we have access to physiological testing? As is often the case, it depends.

The best place to start are the factors that impact performance in your event. What are the demands you will face and where do you sometimes fall short?

Racing a 24-hour event, your muscles are more likely to run out of energy than oxygen. It’s not a hard effort (until it is) but the problem for a vast majority of ultra-runners is energy depletion. Second to that is gastro-intestinal (GI) problems, that also stop you getting energy in.

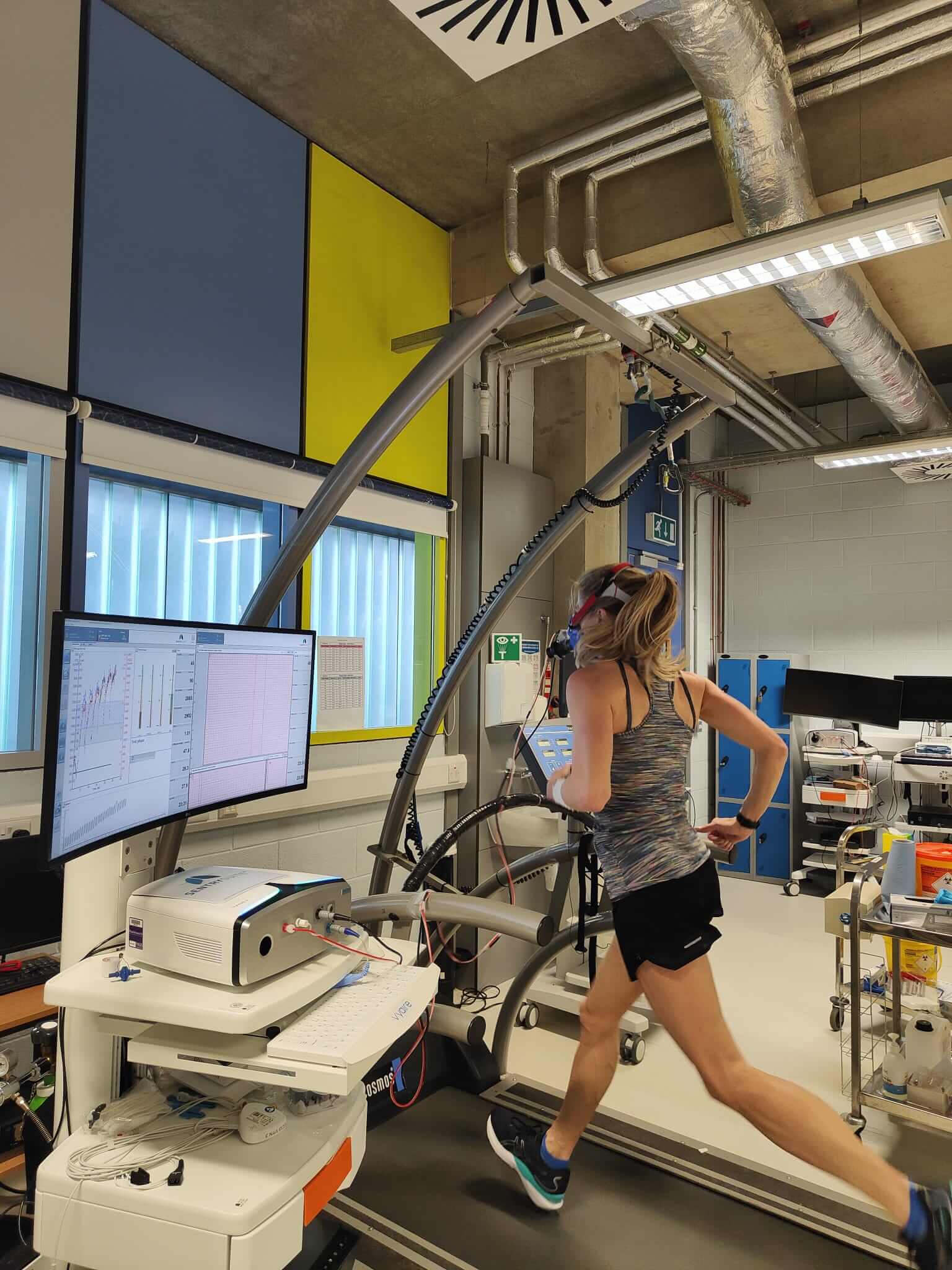

So a 24-hour runner might come in to the lab to look at where their body is drawing energy from at different race paces. Looking at substrate utilisation tells us what percentage of your current energy is coming from muscle and liver glycogen, stored body fats or the food you’re taking in during the race.

If you know just how that changes from 10 to 11 to 12 kilometres per hour (or any speed in between) then you can plan your effort and nutrition more accurately. Coming as close as possible to making sure you’re getting on just enough that you run out at exactly 23:59 and have to push on fumes for that last minute.

Is it that accurate?

Some ultra-runners, especially those who compete on the trails, might say they don’t go for physiological tests because it doesn’t relate to their reality. The race might be hotter, their stress levels higher, or perhaps it’s a mountain event with varied terrain and altitude.

Yes, with all the variables, in reality you’re not going to develop a plan that sees you run out of energy the moment you step over that finishing line. But the plan you develop can come from a greater base of knowledge, and you give yourself the best chance of excelling.

It can help with problem solving too – another key element of a successful ultra-marathon. The better your knowledge of your own body, the more likely you will make a good decision after 18 hours when sleep deprived, hungry and emotional.

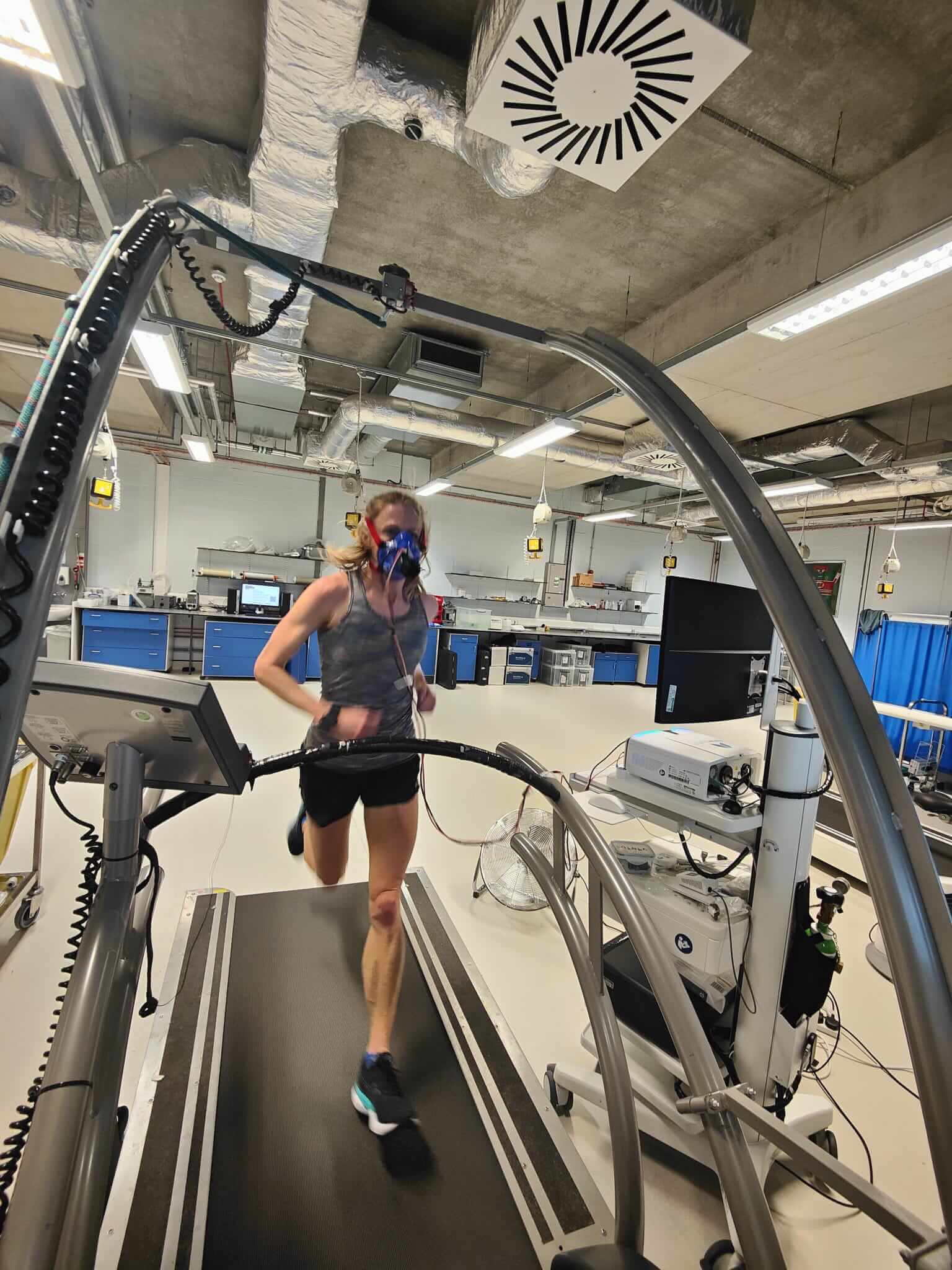

(Hour 7 athlete Caroline Turner in the lab with Dr Jamie Pugh before London and Comrades Marathons)

What about the Heat and Altitude?

As for altitude and heat, you can vary these in the climate and altitude chamber environment. Again, it might be different on race day, but the information can still be very valuable.

Recently we tried to recreate elements of the Western States Endurance Run 100-miler for pro Hoka athlete Hayden Hawks. We had the altitude (and the climbs) of the first five hours on day one, then the next morning we replicated sections of the second half, with lower altitude, similar climbs and the biggest factor, the heat.

Running at similar paces to the year before, where Hayden finished second, we looked at what happened in his body, what he could do differently and took some really valuable lessons for returning in 2023.

It wasn’t perfect for several reasons. The trails were replaced by a treadmill, the downhills were just a consistent flat pace and Hayden is a different fitness (and un-tapered) in November than he will be in Olympic Valley in June.

But this doesn’t remove all value. It doesn’t mean he can’t use the data to instruct his plans around pacing, nutrition, cooling strategies and everything else. It’s just important to recognise these limitations and work with them.

In Summary

Everyone can gain value from physiological testing. A standard lactate threshold and VO2 Max test can be useful, but there is so much more to gain, depending on your event. The value of the lab ultimately comes down to what you take home. And the rewards are available to those with the desire to understand their body and to apply their learning in the real endurance world.